Learning to fly

I‘m walking down the ramp for the first time toward my aircraft's parking spot. There are bright orange planes parked everywhere. It is bright, loud, sweltering, and reeks of exhaust fumes. I waited my whole life for this, the moment I saw in all my favorite movies when the pilot strutted to their aircraft in their flight suit, carrying their helmet and gear, peering steely-eyed through aviator sunglasses, dog tags rattling, and ready to take on the world. I should have been excited, but it was the last place I wanted to be.

This moment is not the beginning of my flight school experience; it started months before in Introductory Flight Screening (IFS).

“Attrition is an expensive by-product in pilot production. Introductory Flight Screening (IFS) is a program established to expose Navy and Marine Corps student pilots to aviation in an aircraft at one quarter of the operational expenses of the Navy’s Primary training aircraft, the T-34 Turbo Mentor, and nearly one tenth of the T-6 Texan (future T-34 replacement). The objective of IFS is to decrease drop-on-request (DOR) and flight failure (FF) rates in Primary flight training by identifying student pilots who lack the determination, motivation, and aeronautical adaptability required to succeed in training.”

IFS was an inexpensive way for the Navy to determine whether someone might quit or fail out of flight school. During IFS, the Navy would send flight school students to local civilian flight schools to fly slower, less powerful aircraft.

“IFS has several milestones required for successful completion. The Student Naval Aviator (SNA) must fly at least 24 flight hours, but no more than 25 hours to include three solo flights with one being a cross-country event. The first solo must be flown by the 15-hour mark which can be extended to 17 if the command review board approves.”

I began IFS training at Pensacola Regional Airport and flew the Piper PA-38 Tomahawk. The PA-38 is a two-seat, low-wing, T-tailed training aircraft produced from 1978-1982. The Tomahawk was introduced to me as the "Traumahawk," aptly named for its terrible reputation.

“Since the two-seat trainer was introduced, it has been involved in 51 U.S. stall-spin accidents that resulted in 49 deaths. It also has been the subject of numerous pilot reports regarding its unpredictable stall-spin characteristics and tendency to enter flat spins. A recent report by the AOPA Air Safety Foundation found that the Tomahawk stall/spin accident rate was nearly double that of comparable training aircraft such as the Cessna 150/152 , Beech Skipper and Grumman AA1. The NTSB’s own comparison between the Tomahawk and the Cessna 150/152 found the Tomahawk’s fatal stall/spin accident rate was from three to five times higher than the Cessna trainer. The NTSB noted that at least seven of the Tomahawk stall/spin accidents that it has investigated “involved inadvertent spins that occurred during instructional flights while attempting slow flight or stall training.”

I learned early in flying the traumahawk that I had difficulty landing. My technique was to panic whenever I got close to the ground, totally freeze up, and hope the plane somehow landed itself. Every landing was different. I bounced off the landing gear, landed too fast, slow or crooked, nose high, nose low, and never over the correct spot on the runway. The only thing my landings had in common was that they were all terrible.

It was clear that I would not make the 15-hour mark for my solo because I was a danger to myself. Luckily, CAPT Pettitt negotiated extra training hours for me, and I eventually met the absolute minimum standard to be "safe for solo." In aviation, it is said, "Any landing you can walk away from is a good landing." - I was putting that to the test. My first solo flight was uneventful, but on subsequent flights, I inadvertently flew into a storm and essentially crash-landed with my wing and tail hanging off the runway. On my cross-country flight, I got disoriented and tried to land at the wrong airport, which happened to be where the blue angels practiced. I completed IFS but knew I lacked the "aeronautical adaptability required to succeed in training." About 5% of Student Naval Aviators failed this training phase and never realized their dreams of being naval aviators. I should have been in that 5%.

So, as I walked to the T-34 Turbo Mentor for the first time, I didn't appreciate that I was on my way to achieving my childhood dream. I was wondering how on earth I would fly a 550-horsepower fully aerobatic turboprop aircraft flying over 150 knots after I demonstrated I couldn't handle the 112-horsepower traumahawk that could barely make it 100 knots. I was terrified, but I had two things going for me.

1) CAPT "Primetime" Pettitt believed in me.

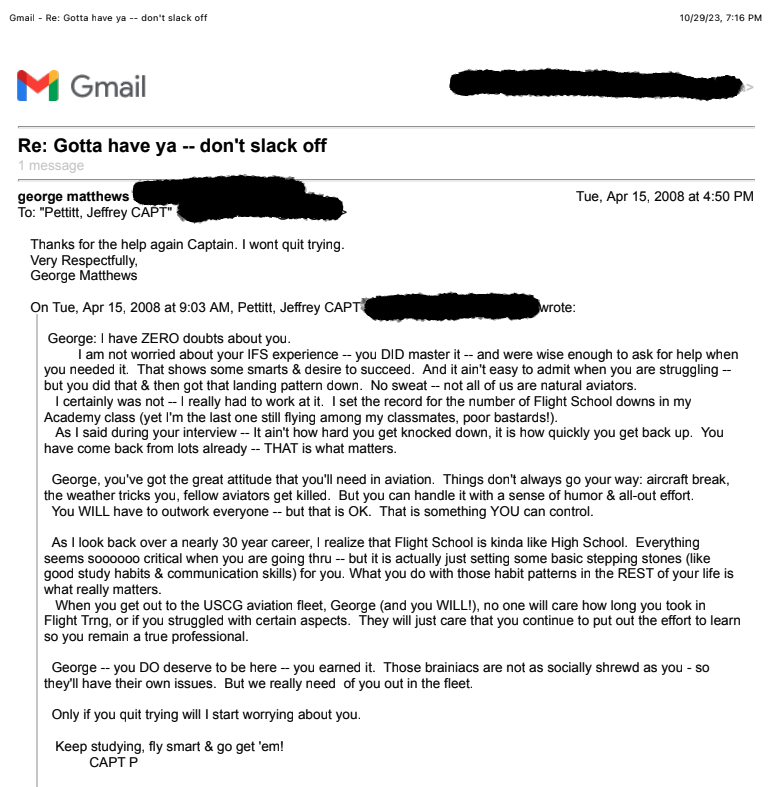

He was a legend in Coast Guard aviation, and for some reason, he saw something in me. After IFS, he knew I was discouraged and sent me this message in an email:

His words gave me the courage to continue when I doubted myself, and I didn’t realize at the time how true his words were.

2) I had a plan.

Everyone ahead of me in flight school mentioned that the key to success during the first flights was to get the aircraft started as fast as possible. It was August in Milton, FL, and temperatures regularly hovered above 90 degrees with oppressive humidity. On the paved ramp with aircraft spitting exhaust, it was much hotter. Inside the cockpit of an aircraft baking in the sun all day, it was likely the highest temperature recorded on Earth. Climbing into the cockpit with a fireproof flight suit, boots, survival vest, gloves, and a helmet, you were trying to cremate yourself. The faster you could do your preflight walkaround, climb into the aircraft, and get it started, the faster you could turn the air conditioning on. The sooner the air conditioning was on, the happier your instructor would be. Experience taught me I was terrible at flying, so I figured I'd better be good at the checklist. I would make an excellent first impression and fool the instructor into thinking I was competent. I practiced that start checklist constantly in the weeks leading up to that flight. I ran through it at home, while driving in the car, and in the cockpit procedures trainer. I knew all the switches, gauges, and procedures by heart, but I failed to anticipate that I needed to practice in a sauna, in winter clothes, mittens, and blindfolded.

I climb into the searing cockpit and begin the checklist. It is an assault on my senses; with double hearing protection, all sound is muffled, touch and dexterity are compromised with flight gloves, and the flight suit and harness feel like a straightjacket. I am sweating profusely. The sweat is running down my face and burning my eyes, and when I look down to read the pocket checklist on my kneeboard, the sweat drips on my visor. My visor is fogged, and I keep trying to wipe it, but it only spreads the sweat and makes the visibility worse. The instructor is sitting behind me, and I see him in the cockpit mirror. He is visibly angry, scowling, and sweaty. I am uncomfortable and start to panic. I feel my heart racing from nerves, the heat, and the fear of actually flying. I unravel. All the preparation on the checklist is for nothing as I fumble through muddling calls, rambling, and making procedural errors.

When you check into primary flight training, you are paired up with an "onwing," an instructor who flies with you on your familiarization flights and ensures you are safe to fly the aircraft solo. My owning was mean. There is no other way to describe him.

So, as I panick, I am encouraged by a barrage of "What in the F#$% is taking so long up there?", "What is your problem?" "Are you kidding me?". My heart is pounding harder. I can’t think, I can barely function, but I keep bumbling through.

After I start the engine and finally get to the most critical step, "Air conditioner—AS REQUIRED," I think I am in the clear, and the cool air gives me a moment of relief. I take a deep breath, and my respite ends abruptly when my onwing notices my parachute isn’t attached. There is a backpack-type parachute in the cockpit, and one of the first steps is to strap it to your body before putting on the 5-point restraint harness.

3. Parachute — FASTENED/ADJUSTED.

4. Restraint harness — FASTENED/ADJUSTED.

I release my 5-point harness, don the parachute, and re-fasten the harness. As my hands tremble and I desperately try to secure my harness, I am lectured about how bad of an idea it was to try and fly without a parachute. My plan of impressing my onwing with checklist mastery is a complete failure. After an eternity, I make it through the checklist, and we are ready to taxi.

I learned in IFS that taxiing an aircraft was more challenging than I imagined. You have to use just the right amount of power to get the aircraft moving and use the rudder pedals to steer.

7.6 TAXIING

Normal taxi is initiated by a slow, straightahead roll using engine power as required to start forward movement. Steering is accomplished by use of rudder control and individual wheelbraking by using positive brake application in desired turn direction. Taxi speed can be effectively controlled by the use of the PCL and applications of propeller beta range.

I try to remember how to get from our parking spot to the taxiway and the runway. You had to memorize a convoluted maze to ensure proper traffic flow, and it changed based on which runway was in use. I have almost no clue where I am going. I apply power, we start to move, and I confidently make a right turn toward the taxiway. Somehow, and I don't know how, I start driving toward the aircraft parked next to us. Because I have been steering a car with my hands since I was 16, my primitive brain takes over and I push the stick hard to the left. The left stick deflects the ailerons and has no effect on the collision course I am on. I freeze. My onwing takes over with his controls and screams at me for several minutes. Not only did I almost hit another aircraft, but I turned the wrong way to begin with.

My onwing taxies toward the runway, I make a couple stammering radio calls, and we line up for takeoff. He jams the power control lever (PCL) forward for takeoff power. I am thrown into the seat with far more force than expected, and the runway rushes by. I think to myself, there is no way I am going to graduate flight school.

My onwing demonstrates most of the maneuvers on the first flight. I am supposed to be paying attention so that I can perform the maneuvers on my next flights, but I just sat there wide-eyed, wondering how I made it this far. Most of the flight is a blur, and I am intimidated by the speed and the power of the T-34. After landing, I am given another opportunity to taxi, and I shut down the aircraft.

My first flight is a total failure. From the moment I walked out onto the flight line, I did the wrong thing at every opportunity. It was a catastrophe.

The Navy manual stated that this initial training block "will not count in student ranking or for track selection. The purpose of the first block is to motivate the student for the Primary phase of training and to provide each student with an opportunity to observe and to adapt to the military flight environment."

I am far from motivated, and it will only get worse.

I'm leaning as far out as possible, trying to see the ground as we cruise at 170 knots and 4,500 feet above the Florida panhandle. I'm nervous because on this flight, I will be entering the landing pattern and attempting to land the T-34 for the first time. I have no reason to believe that this will be an improvement from my crash landings in the Traumahawk. The only things that have changed are my confidence has decreased, the landing speed and complexity have increased, and I've had some flights in the T-34 where I made every possible mistake and was screamed at the entire time.

Part of this flight is an area 1 familiarization. The area around Whiting Field is organized into training areas, and there are detailed course rules describing how to get from Whiting Field to the working areas and Outlying Landing Fields (OLFs). The fun part is that you must navigate from memory without using GPS. Luckily, you are provided a map of the operating area that looks like a treasure map drawn by a kindergartner using the first version of Microsoft Paint. Below this masterpiece, it clearly states, "NOTE: not to scale, do not use for navigation."

During the preflight brief, my onwing tests me on the map, and I draw it from memory on the whiteboard. I assume he will fly me around the operating area and point out landmarks. This is not the case.

As I lean out of the cockpit, most of my brain capacity is dedicated to keeping the airplane upright and somewhat close to my assigned altitude and airspeed. A scattered cloud layer between us and the ground obscures most of the Florida panhandle.

"What is that down there at nine o'clock low?"

I look down between some clouds and have no idea. I'm not even sure what the instructor is asking. I see some fields, trees, and a couple of unknown buildings. I start rattling off wrong answers.

"You should know what that is!"

I can see my owning is getting angry.

"Do you have any idea where we are?"

I don't.

"That is the F**king Chicken Ranch!"

You can see in the treasure map the extremely detailed artist's rendition of a chicken ranch. I drew it perfectly in the preflight brief, but I didn't have the slightest clue what a chicken ranch was. Even if I did, there was no chance I could point one out from 4,500 feet in between some clouds. We play this game for the next 30 minutes. He points at something, I can't correlate it to the convoluted hieroglyphics, and he gets more upset. He ensures I know that I have failed my area 1 familiarization.

Once I am completely disoriented and panicking, he says, "Take me to NOLF Barin." All I know is that I am on the West side of area 1, and I desperately scan, hoping for a miracle. There it is, just to the right of the nose, I can see a clearing with an airport. I act like I knew it was there the entire time and make an easy turn towards it. I start slowing back and configuring the aircraft for landing.

"What are you doing wrong right now?"

This is a tough question. I am sure I am doing plenty of things wrong, but I can't pinpoint what he is referring to. I rechecked all of the landing configuration items and found nothing wrong. Then it hits me. I need to switch frequencies to the airport and make the radio call to enter the OLF. We seem far away, but I tell the instructor,

"I'll just make the call to enter the pattern."

He immediately screams, "If you transmit on that radio, I will break your f**king hand!"

I think the punishment doesn’t match the crime for an early radio call, but I keep driving toward the airport.

"Do you notice anything wrong?"

We are probably six miles out, and I just keep thinking about how I need to make a radio call.

"Negative Sir."

"You don't see a problem here? Are you f**king kidding me?"

He is the most angry I have seen him. I keep looking at the airport, rechecking the procedures, and then I see it.

I messed up.

Instead of the bright orange T-34s I expect to see in the pattern, there are white civilian planes. I am moments away from barging into Jack Edwards’, a civilian airport's airspace. I confess,

"I see it now. It's the wrong airport."

"I have the flight controls. Gs coming on now now now."

I remove my hands from the flight controls as my onwing takes over and immediately banks through an 80-degree turn away from the airport.

At a 70-degree angle of the bank, I experience a rapid onset of three Gs or three times the force of gravity. When the Gs increase, the blood is pulled out of the head until pilots go unconscious. We were trained to combat this with an anti-G straining maneuver, where you squeeze all the muscles in your lower body and breathe a certain way to keep blood flowing to your noggin. We practiced it in a chair in an air-conditioned room.

Currently, the anti-G straining maneuver is the last thing on my mind. I freeze and do nothing. I feel overwhelming pressure on my body, and I flail as my peripheral vision starts to go dark. Moments later, he rolls out, pointing at the correct airport, and all my blood goes back to where it is supposed to be. I feel awful, physically and mentally exhausted, and still haven’t made it to the pattern.

Surprisingly, things don’t improve when I get over the runway. I continue to fall apart and wave off nearly every approach. The few landings I manage to touch down are abominations.

Another complete failure.

My entire life, I believed I could accomplish anything. I believed that my dream of becoming a Coast Guard pilot was not only possible but also my destiny. I believed in myself and focused on the few who believed in me.

After that flight in the pattern, everything changed.

I remembered the guidance counselor who told me I probably wouldn't make it to the Coast Guard Academy.

I remembered the English teacher who told me about much better students who weren't accepted into service academies.

I remembered the moment I got rejected from the Coast Guard Academy.

I remembered struggling through every moment of the Coast Guard Academy.

I remembered my friends all laughing at me when I told them I was applying for flight school.

I remembered those same friends who would joke about how long I would last before I failed out of flight school.

I remembered nearly failing out of IFS when everyone else was having fun.

It wasn't that I never thought about those moments before. I thought about them all the time. The difference was that before this moment, I had always ignored the doubt and looked forward to proving everyone wrong. Now, the doubt consumed me, and I knew I would fail and prove everyone right. I should have never made it this far, and I knew it.

The next few months were among the most challenging and darkest times of my life. Failing seemed inevitable, and I hoped for any way out of flying. I hoped someone would back their car into me, or I would fall down the stairs, or a hurricane would come. I felt lonely, and I was afraid to admit to anyone how badly I was struggling.

I began to self-destruct. I self-medicated with alcohol on the weekends, ate whatever terrible food I wanted, quit working out, and didn't prioritize sleep. My body responded to the stress, and I began to suffer from headaches and repeated sinus infections. I welcomed the sickness because the flight surgeon would take me off flight status, and I would get a break from training. The lack of consistent training, illness, and my terrible attitude resulted in consistently failing flights.

I was scheduled for warmup flights whenever I returned from being sick. I was also given extra flight time after failing events when I was forced to repeat the flights. With these extra reps, I became proficient at the "high work". I could quickly recover from a stall, spin, approach turn stall, or simulated emergency. As I flew with other instructors beside my onwing, they would assume I knew what I was doing until I got into the landing pattern. Despite all the extra flight time, I still had no idea how to land. I was running out of time, and the instructors ran out of patience.

Before you can fly a T-34 by yourself, you must pass the safe for solo check ride. The safe for solo check ride was intentionally the most challenging flight in flight school. The preflight briefing items consisted of any previously briefed item, and the flight was total mayhem. You were tested on every maneuver and emergency possible.

I should have never made it to the safe for solo check ride.

I failed my last flight prior to the safe for solo check ride. I should have failed on my second attempt, but something interesting happened.

I had already failed so many flights that failing this flight twice in a row would trigger a training review board. During a training review board, squadron leadership would meet and discuss whether I should be allowed to continue training or be attrited.

If you failed the notorious safe for solo check ride, that would also trigger a training review board.

Either way it seemed I was headed for a Training Review Board.

During the debrief for my second would-be failure, my onwing tells me how atrocious my performance was, but then explains,

"If I fail you on this flight, you go to a training review board. If you fail your safe for solo check ride, you also go to a training review board. But, if I pass you and send you to your safe for solo check ride, you at least have a chance of passing and will be able to continue training."

I do not have a chance of passing. My onwing is probaly just ready to be done flying with me and can’t take one more flight punctuated by terrifying landings. I am brimming with confidence when I leave the debrief.

When I get home, I compulsively check the schedule and anxiously wait for the details of my check ride. I hope for one of the few friendly instructors, or maybe that they would forget to schedule me entirely. Then I see it, and a wave of panic comes over me. I am scheduled with "The Hawk," the meanest, most feared instructor in the squadron with a reputation for taking pleasure in failing students. If that isn't bad enough, I have the dreaded 0500 brief, meaning I will have to be at the squadron around 0430. I cram as much as possible, and my nerves keep me up all night.

The preflight brief is ruthless, but I do fine. "The Hawk" seems to be slightly impressed with my knowledge, and I begin to feel a small glimmer of hope that I can make it through this flight.

As I strap into the cockpit, I am very nervous, and the mood is tense. I try to lighten things up, and before starting the checklist, I blurt out, "Hey Sir, are you ready to get this party started?" This is a mistake. I look back at him in the cockpit mirror. He looks so mad that it is terrifying. His response to my question was so vulgar that I can't repeat it, but it was clear there would be no party starting.

The flight starts with a barrage of questions about limits, maneuver parameters, and emergency procedures, but I am prepared. Once in the operating area, we begin the usual high work. My stall and spin recoveries are perfect, and he even compliments me, but I know the jig will be up as soon as we enter the pattern.

As soon as we finish the high work, we see an abnormal engine indication. It's strange to say that a malfunctioning engine in an aircraft is a miracle, but right now, it is the greatest miracle I can imagine. We terminate training and fly back. I try to contain my excitement on the way home. I have survived the brief and high work with "The Hawk," and all I have left is the dreaded pattern work. The good news is that it will have to be scheduled for the next day, and any instructor will be an improvement over "The Hawk." Things are looking up for me.

Back at home, I start anxiously rechecking the schedule. I am in pretty high spirits for the first time in a long time. All I have to do is get in the pattern and demonstrate a couple of safe landings. I estimate I can pull off a "safe" landing almost half the time, so I figure I have a decent enough chance of passing this flight and making it to my solo.

Then, in a moment, all hope evaporates as I read the schedule. 0500 brief with "The Hawk". This can’t be happening.

7.14 WAVEOFF

The waveoff is a mandatory signal and will be executed immediately upon receipt; whether it is a red light from the tower, the runway wheels watch by interphone or radio. Pilots should initiate their own waveoff anytime a safe landing is not possible. The decision should be made as soon as possible during the approach to provide a safe margin of airspeed and altitude. Complete the following procedure as applicable. Engine spool-up delays of as much as 5seconds may be encountered after power addition.

1. PCL — FULL POWER.

2. Positive rate of climb — ESTABLISHED.

There is an adage in aviation that "Waveoffs are free." As student pilots, instructors encouraged us never to try and force a bad landing. They emphasized that there were no negative repercussions of waving off an approach. Given that all of my landings were on the edge of unsafe, I was a master at waveoffs. In fact, I'm sure I executed more waveoffs than any other maneuver.

As I enter the landing pattern with "The Hawk," I know all I have to do is a successful full-flap landing, a no-flap landing, and a few emergency landings.

I go through my landing procedures and set power for landing.

"Airspeed below 120, flaps coming down", trim, turn, talk.

I transmit, "Red Knight 830, one-eighty, gear down and locked."

As I turn toward the runway, I feel my heart race.

"Gear down, flaps down, landing checklist complete.”

I approach the landing threshold.

"Gear down and locked, negative lights."

I am almost there. I see the ground rushing up at me as we fly down the runway at 80 knots, and I panic.

"I'm going to wave this one off."

I jam in full power, I’m thrust back into my seat, and I begin to climb. I look back at "The Hawk," and he seems confused.

"That one just didn't feel right. I think I had some winds at the bottom."

I can't tell him I panicked and waved off because I was scared.

I come back around again.

I approach the landing threshold.

"Gear down and locked, negative lights."

"I'm just going to wave this one off too. Didn't feel right." I look back again and "The Hawk" looks less confused and more angry.

"You know that you eventually need to land this thing."

I come around again, determined to complete a landing.

"Gear down and locked, negative lights."

I pull back the power and float just above the ground. My heart pounds, and I wince as the aircraft approaches the runway. We touch down, not on the centerline, crooked, and relatively hard, but it is "safe"! I take a couple of deep breaths as we take back off. "The Hawk" approved of the landing, and I set up for a no-flap landing. Without the use of flaps, the touchdown speed is slightly faster because there isn't the extra lift being produced by the flaps. It should be no surprise that adding speed to my already terrible landings does not improve anything. I am bad at full-flap landings; I am absolutely awful at no-flap landings.

Everything starts to fall apart.

"Waveoff, I thought I might have seen the waveoff lights."

"Waveoff, something didn't feel right."

"Waveoff, I think there was a gusty crosswind on that one."

"Waveoff, I was getting a little slow on that one."

I am unsure how many waveoffs I have done at this point, but I look back at "The Hawk" and know waveoffs are no longer free. He has had enough.

I come around for another landing. I know I need to land this one, or this flight will be over.

"Gear down and locked, negative lights."

Over the threshold, I cut the power and set my landing attitude. I freeze, gripping the controls as hard as I can, and hope the plane lands itself through some divine intervention. Moments later, we hit hard on one of the main landing gear tires with the nose crooked. The other main landing gear crashes down, and the plane ricochets violently from side to side, coming up on one tire as we swerve down the runway. I have had plenty of bad landings, but this was my worst.

"What the f**ck was that?!?"

"I'm sorry."

"Let's try that one again!"

I come around a few more times and continue to land poorly. "The Hawk" has plenty of negative feedback. I know I am not passing this flight.

Finally, "The Hawk" puts me out of my misery, "That's it. We're done. I'm going to fly us home."

We fly back in silence. I know my dream of being a pilot is over.

The next few days are miserable. After failing my check ride, a Training Review Board will decide my fate. Three senior instructor pilots will review my training record and make a recommendation to the Training Wing Commodore to retain or attrite. I hope they recommend attrition because it is the quickest and easiest way out. I have so many more events to get through, and I don't see a way out of the hole I am in. I feel sorry for myself and blame everyone and everything for my failure.

After several long, stressful days, I report to the Squadron Commander in my dress uniform to hear the results of the Training Review Board. The Squadron Commander is a decorated F-16 fighter pilot; he is tall, good-looking, and has just the right amount of swag. I admire him. His office looks like an aviation museum filled with aircraft and squadron paraphernalia, aircraft parts, photos, and newspaper articles. I request permission to enter his office and stand at attention in front of his large desk.

"Please have a seat."

I brace for what would surely be the worst news of my life, and my easy way out.

He looks at me with kind eyes and asks, "How are you doing George?"

I am surprised. I was expecting to be lectured about wasting tax payer dollars and sent home. I thought I was in trouble.

I tell him the truth. "Not great, Sir."

"I can imagine this has been a very difficult time for you. I have reviewed the recommendation of the training review board and spoke to your Senior Coast Guard instructor. We have decided to retain you."

I am shocked.

"When we reviewed your record, we noticed that you weren't able to get consistent training and had several large gaps between events that we think may have contributed to your poor check ride. We also noticed that in every single grade sheet, the instructors noted that you were overly prepared for the ground briefings and had above-average knowledge. It is evident that you are studying hard, and this saved you. We are going to give you a few days off. When you return, we will give you a warmup flight and several extra training flights to prepare you for another attempt at the check ride. I need you to keep studying and we will be able to teach you how to fly."

I am given a second chance, and this is my last chance. He makes it clear that failing any more flights after these extra training flights will guarantee the end of my aviation career.

I am still in the fight.

Later that day, CAPT Pettitt calls. He already knows the results of the Training Review Board because he helped with the decision. He explained to the squadron commander how motivated I was to be a pilot and asked him to give me more time. CAPT Pettitt gives me another pep talk and knows all the right things to say. Despite all my failures, he still believes in me.

I desperately need a night off from studying and decide to relax on the couch with a movie. My roommate had been recommending the Rocky Balboa movie, and I had always loved Rocky growing up, so I throw it on. I admire underdogs, fighters, and people who never quit, and I hope the movie will make me feel good.

In “Rocky Balboa” (2006), Rocky Balboa is retired and running an Italian restaurant in Philadelphia. A computer simulation predicts that he could defeat the current champion, Mason “The Line” Dixon, and Rocky decides to come out of retirement for the fight. At one point in the film, Rocky's son confronts him and shares his doubts. Rocky replies,

““The world ain’t all sunshine and rainbows. It is a very mean and nasty place and it will beat you to your knees and keep you there permanently if you let it. You, me, or nobody is gonna hit as hard as life. But it ain’t how hard you hit; it’s about how hard you can get hit, and keep moving forward. How much you can take, and keep moving forward. That’s how winning is done. Now, if you know what you’re worth, then go out and get what you’re worth. But you gotta be willing to take the hit, and not pointing fingers saying you ain’t where you are because of him, or her, or anybody. Cowards do that and that ain’t you. You’re better than that!” ”

I feel like Rocky knows me, is a part of my story, and says these words directly to me. His monologue immediately snaps me out of the self-loathing I am wallowing in. I realize that it isn't enough to admire underdogs, fighters, and people that never quit, it is time to write my story. I wonder how much I can get hit and keep moving forward.

Overnight, my attitude changes. I wake up the following day determined and ready to work, except I am unsure what to do. My major problem is that I don't know how to study. In high school and at the Academy, I did just enough to get by with minimal effort. I learned well enough to pass the test and move on. That level of studying was enough to get through a preflight brief or the easy parts of the flight, but it wasn't getting me through the pattern when fear took over. I needed to learn the material well enough that I could execute the procedures when everything was falling apart around me. I needed help.

There is an Air Force pilot named Matt in my Squadron. He is breezing through flight school and making it look easy. He is an Air Force Academy graduate; he doesn't drink, doesn't act like an idiot on the weekends, and is not only excelling in flight training but running 100 miles a week. I want to be like Matt, so I ask him if he is interested in studying with me. Up to this point, I studied alone because I was worried that studying with anyone else would make me feel stupid.

I meet Matt in Barnes and Noble's cafe and we study together for hours. We discuss the preflight briefing items, systems, normal procedures, and emergency procedures, and most importantly, we mentally rehearse the flight. In detail, we discuss every button push, control movement, and radio call from takeoff to landing. He asks me questions as I walk him through the flight profile. I tell him about my struggles, and he gives me tips. Matt never made me feel stupid. He made me feel like I would succeed, and I will always appreciate his kindness.

Over the next few days, I take what Matt taught me and practice at the beach. I travel away from all the people, so I don't look crazy and draw the entire operating area in the sand. I add rocks for landmarks and pieces of driftwood for runways. I start at the driftwood Whiting Field and verbally rehearse the takeoff procedures. I walk the course rules, visualizing every point along the flight path. I spend hours in the driftwood landing patterns repeating the landing sequence.

During my break from flying, I study with Matt a few more times and walk the beach aimlessly for a few more hours. I visualize hundreds of perfect flights with beautiful landings.

I establish a new routine where I watch the Rocky speech first thing in the morning. I repeat it to myself throughout the day "But it ain't how hard you hit; it's about how hard you can get hit, and keep moving forward. How much you can take, and keep moving forward. That's how winning is done." I am ready to return to flying and have something to prove.

Major Galluzzo is hand-selected to be my instructor for my extra training flights. Before being a flight school instructor, Major Galluzzo was a Combat Search and Rescue helicopter pilot. He is more senior than most of the other instructors; his hair is a little more grey, his flight suit a little more weathered, and you can tell he has seen some stuff.

"So I heard you are having some trouble with the landings?"

He can tell I am nervous. "Yes Sir, I have been having a lot of trouble."

"That's ok, we're going to fix that."

The way he says it is so confident and reassuring that he could have told me I would be the next astronaut to walk on the moon, and I would have believed him.

He has a calming, easygoing demeanor. He is exactly the instructor I need.

Flying out to the pattern, I am nervous, but I know I have done everything possible to prepare. I had flown the profile perfectly so many times in my head. I just needed to do it in the plane.

I take a slow deep breath.

"airspeed below 120, flaps coming down", trim, turn, talk.

I transmit, "Red Knight 031, one-eighty, gear down and locked."

I take another deep breath. I feel ok.

"Gear down, flaps down, landing checklist complete"

I approach the landing threshold.

"Gear down and locked, negative lights."

I am nervous, but I don't freeze. I think back on all the tips from Matt and hours on the beach. I cut power and float down the runway. I touch down and it is not terrible. I push up to takeoff power and lift off the runway.

Major Galluzzo calmly says, "Not bad, but where are you looking as you're landing."

I have no idea, mostly I just stared blankly at the runway right in front of me.

"I'm not sure Sir."

"Lets work on that. On final, I want you to focus on aimpoint and airspeed. Look at your landing spot and fly the aircraft towards it. Look back at your airspeed and crosscheck that it is staying at 90 kts. Once you start the landing transition, move your gaze out to the horizon. See the runway in your peripheral vision."

The way he calmly instructs puts me at ease and I line up for another landing.

I repeat to myself "aimpoint, airspeed, aimpoint, airspeed"

Just above the runway I pull the power back to idle and look at the horizon. I feel like I am in control and I make minor corrections to my landing attitude while I float down the runway. I touch down gently on centerline. It feels incredible.

"Very nice!"

I take back off and we stay in the landing pattern for the next hour. After each landing, Major Galluzzo calmly identifies small errors and gives me one or two corrections to focus on. I notice improvement on every pattern, but more importantly, with each landing I am gaining confidence. By the end of the flight I am exhausted, but for the first time, I enjoy flying.

I can’t wait for the next flight with Major Galluzzo. We fly together two more times and after five hours and 23 landings, it is time to attempt my checkride. He ensures me that I am ready. I believe him because we didn't stop practicing landings after I made a couple successful attemots, we continued in the pattern until I was certain I would never fail at landing again.

[I never properly thanked MAJ Galuzzo, I searched for him recently to let him know that he changed the course of my life, but couldn't find him. 15 years and three thousand flight hours later, I still try and emulate Major Galluzo as an instructor pilot, because I learned the tremendous impact one passionate instructor can have on a struggling pilot. Thank you Major Galluzzo.]

My checkride is scheduled for November 20th, the day after my last flight with MAJ Galluzzo.

As I walk into the preflight briefing space, I am confident. I write all of the briefing items on the dry erase board and wait for my instructor. I reflect on how far I have come. I am not only a totally different pilot, but a different person. The last month was transformative in every way and instead of nervously cowering before the brief, I can’t wait to show the instructor how far I have come. I am paired with another senior instructor pilot. He asks about the last checkride and how I ended up needing extra flights. I explain my challenges with landing and he reviews my record with me. Similar to MAJ Galluzzo, he is calm and confident and makes me feel at ease.

On the walk to the aircraft, I feel strangely calm despite the fact that everything is on the line during this flight. I run through all the procedures, takeoff, and high work with no issues. Now it’s time for the pattern. I think back to CAPT Pettit, Matt, Major Galluzzo and all the people who believed in me and helped me get to this moment. I won’t let them down. As I approach the landing pattern I am confident and intensely focused.

"airspeed below 120, flaps coming down", trim, turn, talk.

"Red Knight 252, one-eighty, gear down and locked."

I am nailing every checkpoint.

"Gear down, flaps down, landing checklist complete"

I repeat to myself "aimpoint, airspeed, aimpoint airspeed"

"Gear down and locked, negative lights."

Power out. Flare. Look at the horizon. Time slows and I make micro adjustments to the landing attitude. I land successfully.

I stay in the pattern and perform the rest of the landings and emergency landings. Each landing feels smooth and effortless. When the pattern is complete, we fly home and I feel extremely proud of how far I have come.

After the flight the instructor says "I have very little feedback for that flight. All of your procedures were great. Your pattern work was above average and you had absolutely no issues with your landings. I'm not sure how you could have failed your checkride to begin with. "

On Nov 25th 2008 I flew my solo in the T-34, but I still had a long way to go.